Messages to the Future

by Bea Lebal

A poem. A diary. A letter. The minutes of a meeting. A text message. There are many kinds of written records. Each document has an immediate purpose, but sometimes—whether intentionally or inadvertently—it becomes a message to the future as well.

During a twenty-year career as Director of T.B. Scott Library in Merrill I did a lot of writing—from memos to minutes and grant applications to annual reports. Some items were the work of a few minutes; others carefully crafted because I knew they would be archived along with other important documents that, together, tell the history of a well-loved municipal institution. I had a personal reason to respect the importance of the official records of the library. Long before I was hired by the Library Board of Trustees, I used the library archives to research and write my library school master’s thesis about the early years of the library’s history.

As a member of the Merrill Historical Society Board of Directors for more than two decades, my duties have gradually increased and I am now President and a curator of collections. Through this association, my adopted hometown’s past captivates me.

Several days a week I work at the museum, performing tasks from custodial to fundraising. As a curator, I’ve found the collections in even a relatively small museum like ours seem to offer unlimited opportunities to discover interesting stories. The archives give me access to many kinds of print resources: diaries, scrapbooks, photo albums, letters, government documents, school yearbooks, minutes, newspapers, etc. Unlike the library’s archives, which focus on a single entity, historical society archives include records from individuals, businesses, nonprofits, educational and religious organizations, as well as our own Society’s files. Along with historic artifacts that tell tales in their own way, these written records motivate me to find and share stories—messages from the past waiting to be discovered.

When a story catches my attention, my goal is to rescue it from obscurity and give it new life. The diaries, letters, and memoirs stored in our collections have particular appeal for me. Linking these very personal historic writings to other, complementary documents and images gives the stories a wider context; it is my way of giving messages from the past meaning for today’s audience.

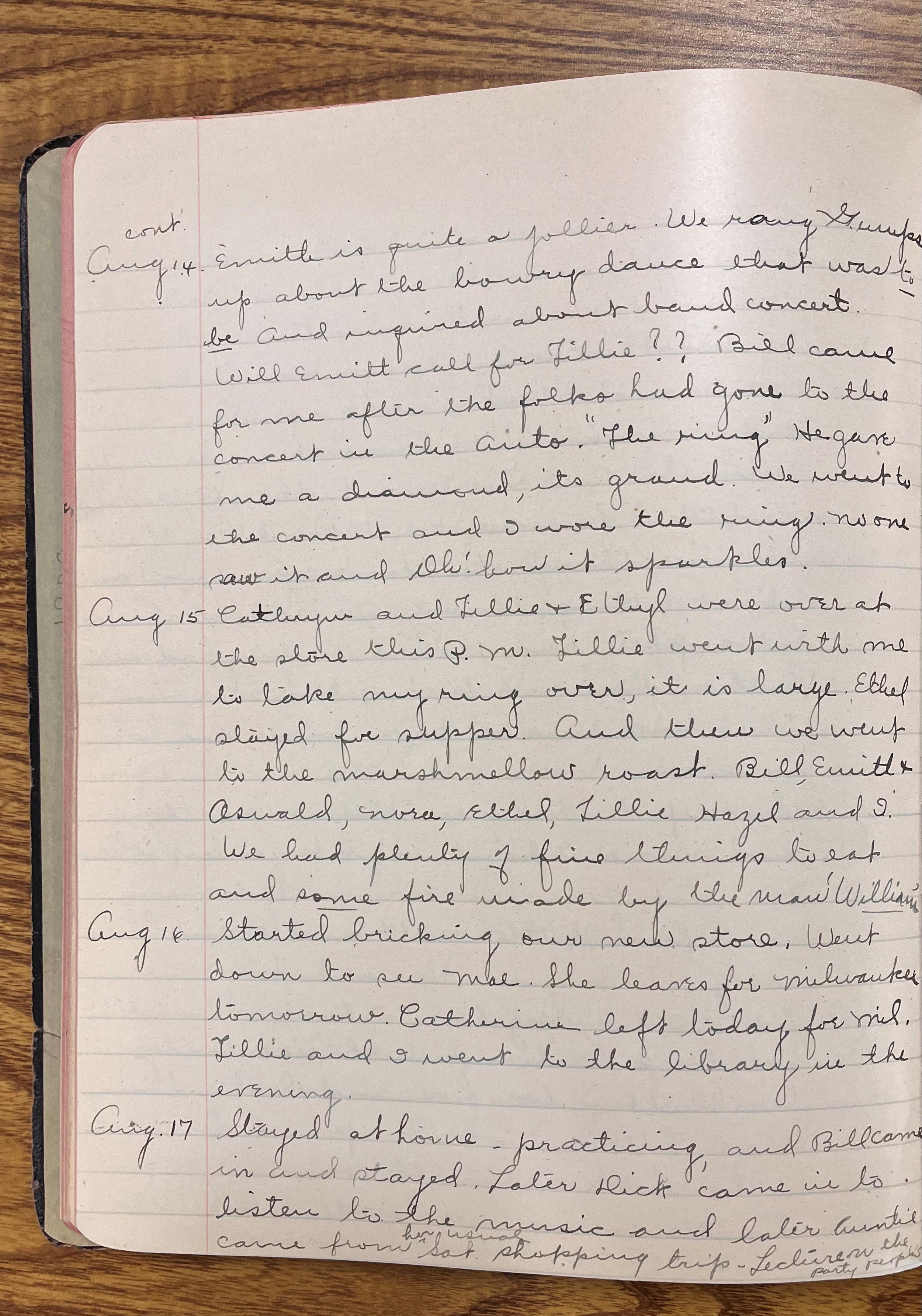

One of the first treasures to capture my interest was a plain, black-covered, blue-lined composition book—not very appealing on the surface. Beneath the simple title on the first page—Diary—a young woman named Miss Fern Bisbee signed her name and noted that the year was 1910. Her first entry was written on Sunday morning, July 24; she wrote her last entry on June 14, three years later. In between, Fern tells about herself, her immediate family, and daily life in a small Wisconsin town in the early 20th century.

Fern’s mother died shortly after Fern reached her first birthday. Her father earned a livelihood as a logger and saw filer, an occupation that caused him to move often around the Wisconsin north woods. To give Fern a stable home, he brought her to Merrill to live with his older brother’s family. Merrill in the 1890s was a bustling city of about 8,700 residents, transitioning from an economy based largely on the logging/lumbering business to a more diversified economy. Bisbee family members started businesses that helped advance that change, and Fern herself spent many hours working in her father’s hardware store.

The diary tells a touching coming-of-age story. I have read Fern’s diary multiple times watching as a capable, mature woman emerged from an immature girl. I saw her fall in love and then abandon her diary on the eve of her wedding as being a no-longer-relevant remnant of her youth.

Fern depicted many trips in her father’s Buick, one of the first cars in Merrill. In those early days, the mix of new vehicular technologies with roads incised by old-fashioned horse and buggy traffic could turn auto rides into frustrating—or hilarious—adventures. Fern’s descriptions of their motoring experiences prompted me to read an unpublished memoir written by Norman Chilsen, the man who opened our city’s first auto dealership in 1908. I became eager for others to enjoy this local history gem; it was interesting, informative, and frequently laugh-out-loud funny. Chilsen was an excellent writer; along with some minor editing, my contribution was to acquire several dozen contemporary postcards, photos, and ads and use them to bring color and period appeal to his story, told in my book, To Run without Horses.

I had been working at the historical society for several years before I noticed the plain wooden file box. Looking inside, I found dozens of carbon copies of typewritten reports from Pinkerton Detective agents. I was astonished! My second book, Strike! The Pinkerton Papers-Industrial Espionage in 1920 Merrill, Wisconsin, explores this critical episode in Merrill’s history, a story that had remained hidden for decades.

The reports revealed that the agents had come to Merrill to infiltrate the lumber union, collect information for local mill owners who feared a strike over the eight-hour day, and (unsuccessfully) prevent the strike. The book incorporates portions of the detectives’ reports, including reports written by two women detectives. Interestingly, it was the mill owners who recognized that the attitudes of mill workers’ wives were critical to the eventual outcome of the strike action. They requested the Pinkerton organization to send female agents, who then tried to manipulate the feelings of the local women.

To tell the “rest of the story,” I included information about the city of Merrill at that point in time, the history of the mills, union organization and activities, residents’ viewpoints of the strike, thoughts about the aftermath of the strike in our community, numerous photos, and other ephemera. I wanted to capture some of the intrigue and subterfuge of the strike: false identities, clandestine meetings, hidden agendas, and underhanded tricks. Who knew there was industrial espionage in Merrill a century ago?

The stories of the Pinkerton Detectives in Merrill, or Ms. Bisbee, were real-life mysteries as I worked to piece together newspaper snippets or identify faces in a faded photograph. Historical research is not necessarily easy—even for someone who works in a museum—but it is endlessly fascinating.

Several years ago, I presented a PowerPoint program about Fern Bisbee and her diary. I thought that would end my interaction with her story, and yet something has continued to draw me back. In fact, I’ve done so much research on her family that I’ve been named an honorary Bisbee! The diary itself is interesting, but learning about her large, complicated family and its role in Merrill’s history has added immensely to my appreciation of Fern’s narrative. Sometimes I wonder if Fern grasped the importance of her own story.

Certainly, Fern could not have foreseen the tragedy in her future when she wrote her final diary entry. The death rate in the overall population of the United States dropped dramatically during the first decades of the 20th century, with one exception: deaths from childbearing increased during those years. Fern was among the victims. She died at age 27 from complications of her second pregnancy. When I first read her newspaper eulogy I felt as shocked as if a close friend had died unexpectedly. That is the effect her simple diary had on me, more than a century after it was written. That is the reason my next book will tell her story.

Historic records are full of latent stories. I encourage you, no matter your preferred literary genre, to explore resources from your local historical society or library and use them to inspire and inform you as you create your own messages to the future.

Bea Lebal, a retired public library director, is now President of and a collections curator for the Merrill Historical Society. Writing is a slow process for her, as other interests frequently intervene. Her two books, Strike! The Pinkerton Papers; Industrial Espionage in 1920 Merrill, Wisconsin and To Run Without Horses focus on stories that at one time garnered headlines in her adopted hometown, but over the past century were forgotten. She is (slowly) working on her third book.