Making & Sustaining Life:

Cherene Sherrard’s Grimoire

by C. Kubasta

Cherene Sherrard’s poetry book Grimoire (Autumn House Press, 2020) begins with a note: “certain italicized sections [ . . . ] are transcribed and/or adapted from one of the earliest cookbooks published by an African American woman: Mrs. Malinda Russell’s A Domestic Cook Book: Containing a Careful Selection of Useful Receipts for the Kitchen (1866).” The book’s dedication is “For the mothers” – and a grimoire is a book of spells. The poems in Sherrard’s book retrace and remake recipes (in Russell’s cookbook, called “receipts”), address the reader – who here is also a maker of cakes, a taster, an eater, a provider of sustenance and pleasure to family. In poems like “Sycorax’s Lament,” the poem engages with Russell’s text among the questions of another son, the comparisons of fruit:

My son wants to know why a fruitcake

has so little fruit in it. Malinda calls for

one gill rose water, one wine-glass brandy,

currants, raisins, and citron, which is like

a lemon in the same way that a cherry is

like a raspberry.

A poet knows from her fruit, the intricacies of taste, the ways something can be “like,” but in no way the same. A poet knows that to overlayer texts is to overlayer versions of the world and ask what doesn’t translate, what isn’t enough, what cannot sustain, no matter how much care in the making. Sherrard’s work explores Black female representation in mid-nineteenth to early twentieth American literature and visual culture; she teaches at Pomona College, and previously taught at UW-Madison. She notes the “stories embedded in recipes engage multiple literary genres, including the how-to-book, memoir, history, autobiography, and fiction.”

The book is richly detailed and richly peopled. The poem “Things to Do with Ginger” begins with “Three kinds of ginger blent in the bowl / I stir while wearing a white evening gown,” and moves to a desert island, invokes the S.S. Minnow, and writes a new episode for Gilligan’s Island: Mary Ann is set “out to sea [ . . .] / sharks tearing at her manicured toes, / drawn to the crimson polish that must / have been her one personal item.” Many of the poems are intertextual – Sycorax (of the above poem) is Caliban’s mother, absent from The Tempest. Another poem is dedicated to John Brown’s first wife, who died in childbirth. I asked about these conversations in the poems, and Sherrard replied:

“I do write in conversation with other artists, writers, and historical figures. Nina Simone’s music was a consistent soundtrack as I was drafting, along with the folk music of Rhiannon Giddens and Martha Redbone, who has an amazing album comprised of songs composed from William Blake’s poetry. I frequently teach writings and the experiences of nineteenth century African American women and the material in the archive can be scarce. There’s a long history of black poets excavating the past and writing into the gaps: see Robert Hayden, Rita Dove, Marilyn Nelson, Elizabeth Alexander, Tyehimba Jess, Natasha Trethewey, and Amaud Jamaul Johnson.”

Grimoire’s poems are undergirded by care, a reconsideration of ingredients, careful and clear instructions, whether talking about making food or caring for sons, or attempting magic. Poems like “Grimoire” are direct: “Mirror, Mirror: . . .” it begins, half-fairy tale, “show me that world / where . . .” and moves to directive. The poem “[To Make] Magic” is a list of ingredients, and this reader wonders if we’re into a different kind of instruction manual now – there are no amounts, no further instructions about what to do with these liquids and spices, their names all potential. The pairing of cookbooks and magic books suggests potential, power, and more. According to Sherrard, “A grimoire, like a cookbook, is an instructional manual. But as any parent will tell you, manuals for childrearing, like the ubiquitous What to Expect When you are Expecting, often fall short in the actual moment. They are all about anticipation and imagination. Similarly, these poems also anticipate and imagine, which is a kind of spellcasting.”

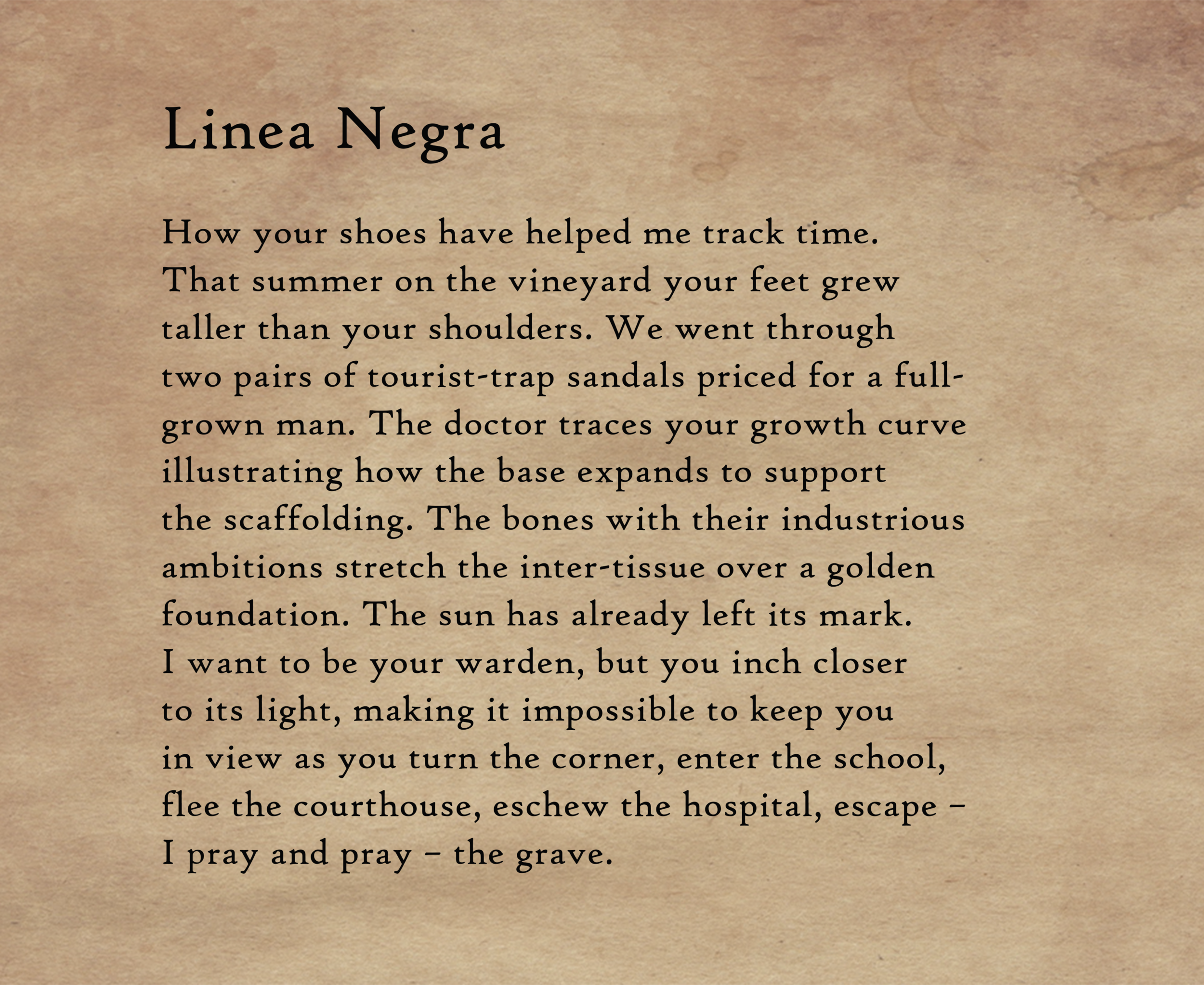

The second section of Sherrard’s book brings motherhood into sharper focus. It begins with two epigraphs: a statistic about Black infant mortality rates as compared to white infant mortality, and an excerpt from Nella Larsen’s Quicksand. Here the poems are mapped on the mother’s body, like “Diastasis Recti” above, or “Linea Negra.”

“During the COVID-19 pandemic, lack of resources exacerbated an already fragile, underfunded health care system,” Sherrard writes. “The most vulnerable humans bore the cost. I began this book thinking about how Malinda Russell, nineteenth-century Black mother, dreamed that sharing and marketing her recipes could provide a sustaining life for herself and her disabled son at tumultuous time. This collection was a way to celebrate and commemorate her ingenuity in the kitchen, and in surviving the perilous geographies of antebellum era.”

There’s a central poem (located centrally in the book) in Grimoire that also drew my attention – an erasure. Erasures are a fascination of mine, something I’ve enjoyed working with, and teaching, and am now wrestling with, holding powerful specimens in my mind (Nicole Sealey, Isobel O’Hare) and the important cautions about redaction as silencing (essays by Solmaz Sharif, Muriel Leung). Sherrard notes the erasure “Head Soup” can serve as a “codex or key to matters at the heart of the collection.” Re-reading it in this way, certain lines mean differently . . . as Sherrard notes, “the redaction is an acknowledgement that even a tribute can do a kind of violence.” I’m back to thinking about making, and magic, and also mothers. To write a poem like “Apricots” – to meld the promise of a fruit’s sweetness, with the way we measure a pregnancy’s progression, and the small ways we hold each other in grief unfolding: “I pressed my cheek / against your ear and wished you happy birthday.”

Cherene Sherrard was born in Los Angeles. She is a Professor and Chair of English at Pomona College. For twenty years, she taught at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she was the Sally Mead Hands-Bascom Professor of English at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.She is the recipient of many fellowships and awards including a Wisconsin Arts Board Grant in poetry and a National Endowment for the Humanities Award and 2019 Outstanding Women of Color Award. Grimoire was a New York Public Library’s Top Ten Poetry Books of 2020. Learn more about her on her website.

C. Kubasta writes poetry, fiction, and hybrid forms. Her most recent book is the short story collection Abjectification (Apprentice House, 2020). Find her at www.ckubasta.com and follow her @CKubastathePoet