Out of Poetry from Dreams

by Tom Davis

In Greek mythology, Pegasus, the white flying horse, once struck the ground on Mount Helicon and created a spring sacred to poets. If you drank from that well, inspiration would strike, and one or more of the seven muses would enter you, and you would write poetry that could echo into the heavens through time. Poets courted madness drinking from the Hippocrene well, but if they could manage, deep within themselves, the power of the muse that entered them, enchantment would flow into their bodies and enter the stories, lyrics, and lines they wrote.

The theme of this issue of Bramble is “dreams–their intelligence, their prophecy, their strangeness.” Poets who have written poems arising from dreams reads like the who’s who of American, English, and world poetry: John Donne, William Blake, Edgar Allen Poe, Emily Dickenson, Walt Whitman, W.B. Yeats, John Berryman, Pablo Neruda. The list goes on and on. Sometimes prophetic, sometimes mystical, sometimes nightmarish, sometimes reaching back into ancient myths or delving into the deepest parts of individual poets, these poems peel away everyday consciousness and reach for realities not accessed by the utilitarianism of logic. They rhythmically alter perceptions that govern who each of us believe we are and give us a glimpse into phantasma buried inside human beings since time began.

A writer from the 1600s, Richard Burton, in his book, The Anatomy of Melancholy, claimed that the border between madness and poetry is a thin one. The border between dreams and wakefulness can be shattered, and the shattering can lead to depression, addiction, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or other madnesses. Throughout history those who found poetry and the power it represents irresistible enough to lead them to sit alone as the sun descended on the horizon to attempt to write a poem have had to deal with a common perception that poets are mad. If you write poetry, you are just not a regular sort of person.

Still, in every age, from the earliest days of oral language, poets have written poems that have inspired, titillated, outraged, expressed the spirit of who whole peoples or whole generations are, or given insights into the innermost emotions, thoughts, and dreams of those who share our world. These insights are outside of our own thoughts and dreams. They expose us to the innermost being that those who are other-than-our-selves have danced into awareness, enriching humanity with beauty, ugliness, adventure, love, fear, joy, grief, prophecies, lessons, warning, and the possibility that the unfathomable can be understood and even, at least sometimes, appreciated.

Some cultures embrace their poets. The Maori in New Zealand, for instance, love to sing and perform and to embrace their poets. A poet’s funeral in Russia, at least in the past, would draw hundreds if not thousands of mourners, and the stories of the huge crowds that would come to dramatic readings by Yevgeny Yevtushenko, the Soviet Russian poet, are legendary. In the ancient Celtic White Goddess culture, poets carried the power of both religion and the political organization of that time in their words, lines, and stanzas as they walked from campfire to campfire and castle to castle. In Asia, Africa, Europe, pre-European North American, and the islands of the Pacific poets have had a special place among their peoples.

In today’s United States an axiom says that there are more writers than readers of poetry and more readers than those who buy poetry books or journals. Since there are poets in every hamlet and city of Wisconsin, poets are not as “other” as they have been at some points in American culture. There was a time when the popular press used to announce that Poetry is Dead since it has no use to the larger society.

Yet, those poets who are serious about their craft and art, who try to drink from the Hippocrene spring made when Pegasus struck its hoof into the earth, dig deep inside their spirits as they court the true power of the muses. When they invoke their "dreams—their intelligence, their prophecy, their strangeness" into their poetry and start exploring those regions in the psyche of either culture or their selves, they test the boundary between inspiration and madness, the fullness of a poet's life, and the ancestry of poetry stretching back into the dimness of history, the spirit of who the poet is and what they may become. The poems published in this issue necessarily come out of that courage as they move the strange power of dreams into the incantation and power of poetry.

May the readers of this issue inculcate that spring water from Mount Helicon into themselves. May they see beyond the boundary of today into the realms, beyond their everyday reality. May they understand poetry’s true magic.

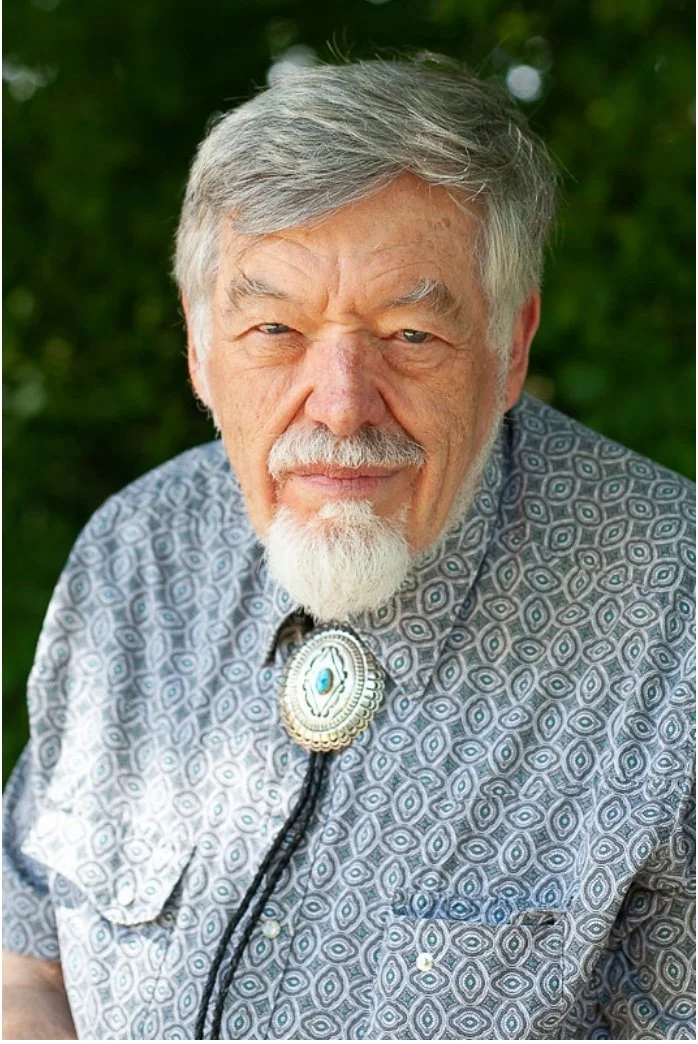

Thomas Davis has published two epic poems, poetry, five novels, and one non-fiction book. His latest book of poetry, Mythos of the Door, has just hit the bookstores. His novel Prophecy of the Wolf will be released in April.