—For Sue Reed Crouse

i.

Remember below that bridge jammed with storm-

wrack, how delighted you were with our find?

Dodder, you exclaimed, that’s dodder! What

could be odder than dodder, which loses

its roots when attached to a host plant,

casts a loose orange net over its capture?

Today by the river I saw brush so

thickly wound with dodder it looked like

forkfuls of some devilish spaghetti,

a comparison putting me squarely

in the tradition of those folk botanists

who bestowed on dodder names of such wild

panache I can only hope that reading them

will make you smile at their found poetry.

ii.

strange tare

scaldweed

beggarweed

lady’s laces

fireweed

wizard’s net

devil’s guts

devil’s hair

goldthread

hailweed

hairweed

hellbine

love vine

strangleweed

angel hair

witch's hair

iii.

So we’ve historically found dodder

unlovable: free-riding, parasitic,

chlorophyll-poor, utterly vampiric

on the sugars and starches it taps with its

piercing haustoria. Unlovable, yet

I believe you in some way truly love

dodder, even dodder, one of those unlovables

we’ve often agreed deserve poems too.

We can acknowledge destructiveness while

being caught in our own net of beauty

the language we both love throws over things —

that love of language more than anything

perhaps the secret of our poets’ hearts’

impractical devotion to this world.

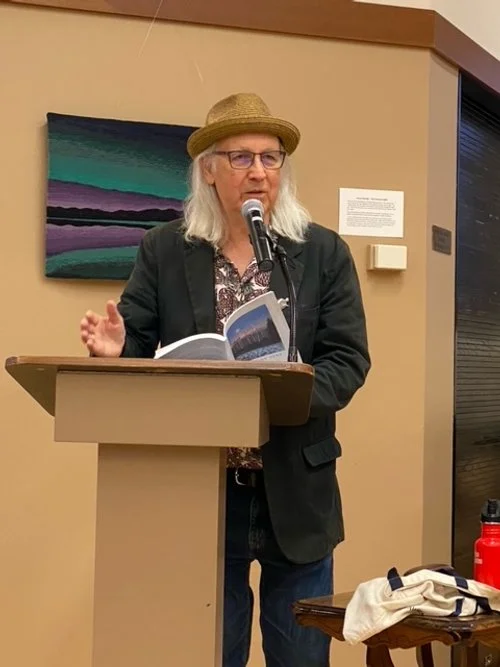

Thomas R. Smith lives in River Falls, Wisconsin, on the banks of the Kinnickinnic River. His most recent books are Medicine Year (poetry) and Poetry on the Side of Nature: Writing the Nature Poem as an Act of Survival (prose). He posts poems and essays at www.thomasrsmithpoet.com.